Page builders have offered a styling panel full of CSS inputs since the beginning of their existence. The idea was that mapping all CSS properties to inputs would make it easy for beginners to manage styling.

While inputs do make life easier for beginners, they come at a tremendous cost in most page builders.

In this article, we're going to take a look at the benefits – and the long list of negatives – that come with CSS inputs. We'll also look at how we're re-architecting CSS inputs in Etch to give users all the upsides with none of the downsides.

The Benefits of CSS Inputs in Page Builders

Inputs have the following advantages over writing CSS:

- They empower users to style a website without having to remember property names or CSS syntax.

- Interacting with CSS inputs can be quicker in many scenarios than writing out CSS, making users more productive.

- They add convenience when applying breakpoint styles, as users don’t have to write and manage media queries in CSS.

These upsides are why are a lot of users continue to rely on CSS input fields for styling in web design. But, after also using this workflow for many years myself, I finally concluded that the cost is too high.

The Downsides of CSS Inputs in Page Builders

You can't just focus on the benefits of CSS inputs. While the benefits are great, it's important to ask, "At what cost?"

Here are the downsides:

- Inputs scatter your CSS across dozens of panels, accordions, and tabs. This creates a big “Where is my styling coming from?” problem. This is especially true when you start factoring in hover states, breakpoint styling, and so on.

- Hunting down the location of a specific CSS input is often slower than just writing the CSS. In some scenarios, CSS inputs are faster, but there are many scenarios where inputs are much slower.

- Inputs can’t always get the job done, which forces the user to write custom CSS. Now you’re in a situation where some styling is placed in inputs while other styling is placed in CSS. This dramatically worsens the “Where’s my styling coming from?” problem.

- If the page builder doesn’t offer a dynamic root selector for writing custom CSS, it creates a situation where the user’s custom CSS is breakable if class names ever change.

- Inputs often generate poorly optimized or “bad practice” code. For example, a CSS Grid input for 3 columns might generate

1fr 1fr 1fras a value, where best practice would berepeat(3, minmax(0, 1fr))orminmax(0, 1fr) minmax(0, 1fr) minmax(0, 1fr). The user has no way to fix this – they’re at the mercy of the page builder. - CSS changes and evolves rapidly and page builder interfaces struggle to keep up. Relying too heavily on CSS inputs means using old and typically inferior techniques.

- Most page builders don’t have a true selector system. At best, they have a single-class system. The ones that do offer a more robust selector system have issues with UI/workflow complexity. The base reality is that you often can’t use inputs to do what’s easily achievable with CSS.

- Page builder developers are incentivized to over-engineer many inputs, adding unnecessary complexity and limitation. This is because certain levels of complexity are cheered by many users as appearing “advanced,” “well-designed,” or “detailed,” etc.

- CSS inputs often have a unit selector and even limit users to specific unit values. In the worst builders, for example, using CSS variables is either not permitted or there isn’t enough real estate to make them practical. The limitations range from “annoying” to “this is an absolute atrocity.”

- CSS inputs dramatically slow down development, add a ton of complexity and technical debt, and take a huge amount of resources away from more important features and innovations. This is because there are hundreds of them, many require very special design and handling (especially if they’re being over-engineered), and there’s quite a bit of conditional logic involved with displaying them as well. If users just wrote CSS and didn’t need inputs, all that engineering time could be spent on more impactful features.

As you can see, the list of negatives far outweighs the positives. This is why I moved to writing all CSS by hand in my page building workflow and started ignoring the input fields completely.

How Etch is Turning CSS Inputs Into a Truly Useful Feature

If we keep the upside of CSS inputs and get rid of all the downsides, they'll be awesome, right?

Let's take the cons one point at a time and see how we're doing things differently in Etch to give users all the payoff with none of the costs.

Inputs scatter your CSS across dozens of panels, accordions, and tabs. This creates a big “Where is my styling coming from?” problem. This is especially true when you start factoring in hover states, breakpoint styling, and so on.

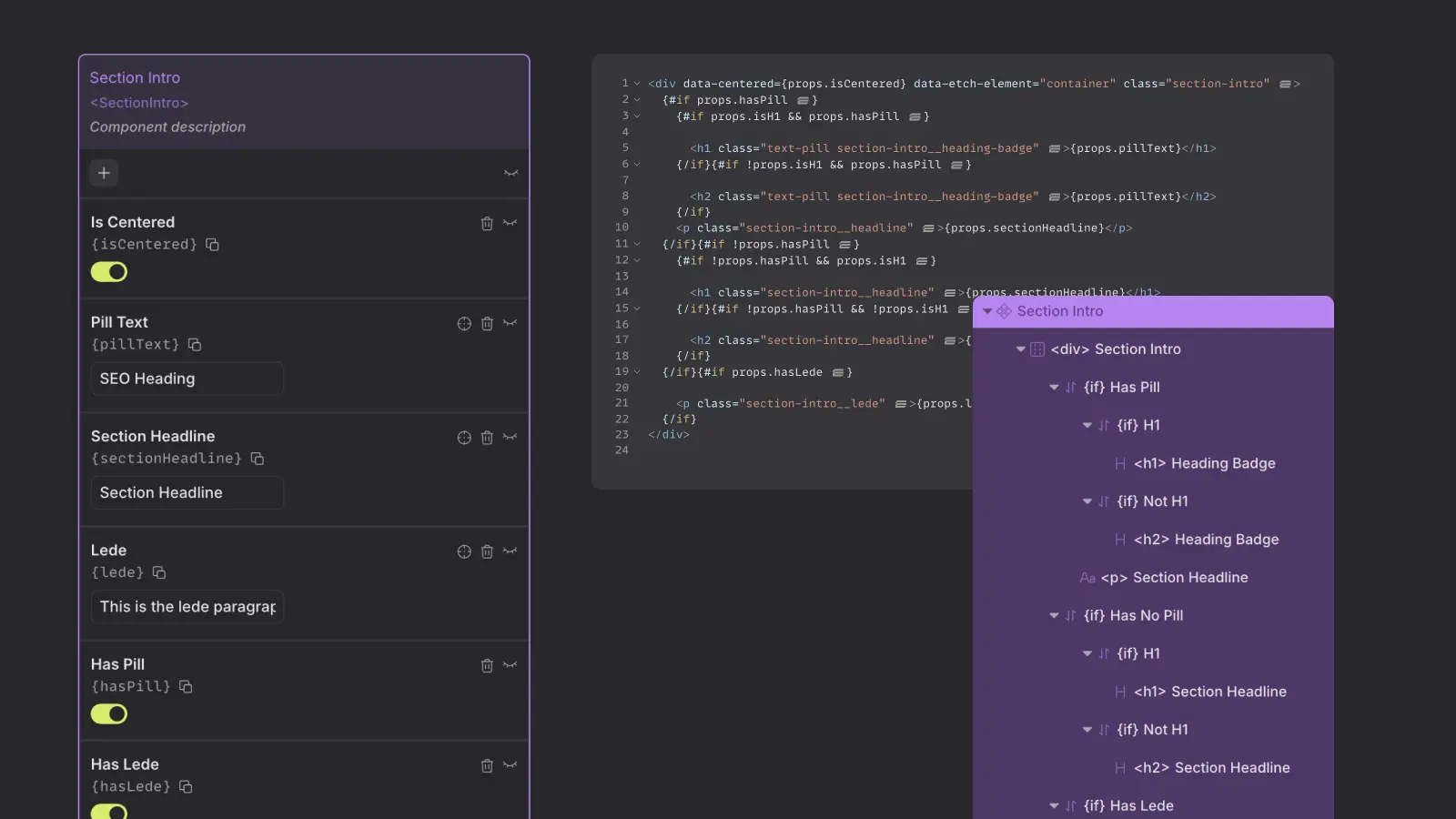

Etch automatically authors all CSS input styling to the CSS editor for each element. It also syncs it bidirectionally, so changes made in the CSS editor reflect back to the inputs. This creates a single source of truth for all your styling.

Hunting down the location of a specific CSS input is often slower than just writing the CSS. In some scenarios, CSS inputs are faster, but there are many scenarios where inputs are much slower.

And…

Inputs can’t always get the job done, which forces the user to write custom CSS. Now you’re in a situation where some styling is placed in inputs while other styling is placed in CSS. This dramatically worsens the “Where’s my styling coming from?” problem.

In Etch, users can opt for a "input-first" workflow, a "css-first" workflow, or a simultaneous workflow.

This means that you can use inputs for everything, write CSS for everything, or use inputs for whatever you think is fastest and then write CSS for the rest. It's the best of both worlds.

If the page builder doesn’t offer a dynamic root selector for writing custom CSS, it creates a situation where the user’s custom CSS is breakable if class names ever change.

Etch dynamically references the selector you're styling so that you're never in a situation where your CSS will break when you edit class names.

Inputs often generate poorly optimized or “bad practice” code. For example, a CSS Grid input for 3 columns might generate

1fr 1fr 1fras a value, where best practice would berepeat(3, minmax(0, 1fr))orminmax(0, 1fr) minmax(0, 1fr) minmax(0, 1fr). The user has no way to fix this – they’re at the mercy of the page builder.

And…

CSS changes and evolves rapidly and page builder interfaces struggle to keep up. Relying too heavily on CSS inputs means using old and typically inferior techniques.

Etch is cutting edge and will stay that way. It will produce the code you expect it to produce. But, if for some reason it doesn't, you're free to just write the CSS yourself to get the specific value you'd like.

Most page builders don’t have a true selector system. At best, they have a single-class system. The ones that do offer a more robust selector system have issues with UI/workflow complexity. The base reality is that you often can’t use inputs to do what’s easily achievable with CSS.

Etch has the most powerful selector system of any page builder ever created. It also happens to be really easy. So there's really no limitation here.

Page builder developers are incentivized to over-engineer many inputs, adding unnecessary complexity and limitation. This is because certain levels of complexity are cheered by many users as appearing “advanced,” “well-designed,” or “detailed,” etc.

We are fully aware of the over-engineering problem. This is why we're handling every single input on a case-by-case basis, starting with the premise of, "Make it as simple as possible and only add complexity if the workflow proves that it's necessary."

CSS inputs often have a unit selector and even limit users to specific unit values. In the worst builders, for example, using CSS variables is either not permitted or there isn’t enough real estate to make them practical. The limitations range from “annoying” to “this is an absolute atrocity.”

We've completely ditched unit selectors. They're terrible. Etch validates values for you, but doesn't limit them.

CSS inputs dramatically slow down development, add a ton of complexity and technical debt, and take a huge amount of resources away from more important features and innovations. This is because there are hundreds of them, many require very special design and handling (especially if they’re being over-engineered), and there’s quite a bit of conditional logic involved with displaying them as well. If users just wrote CSS and didn’t need inputs, all that engineering time could be spent on more impactful features.

The reason Etch's development is moving so fast is because we're laser-focused on critical features and not wasting unnecessary time on secondary or tertiary features.

To us, CSS inputs are a secondary feature. They're at the top of the priority list in terms of secondary features, but we're willing to start very basic here to maximize time spent on primary features.

Once we have the basics nailed down, we'll go through an iteration process to make certain inputs more robust (as needed) and perhaps easier for beginner and intermediate users.

This iteration process will take place over many months, but will never stop the development of primary and critical features. After all, inputs are a "helper" feature. Even if they didn't exist at all, users who know the fundamentals of web design are still fully empowered to do their work.

If you're a beginner or intermediate user who relies on CSS inputs, know this: We'll have them, your workflow will be lightning fast with them, and they'll be architecturally superior to any other tool with all the upsides and none of the costs. They just might lack some "fanciness" out of the gate.